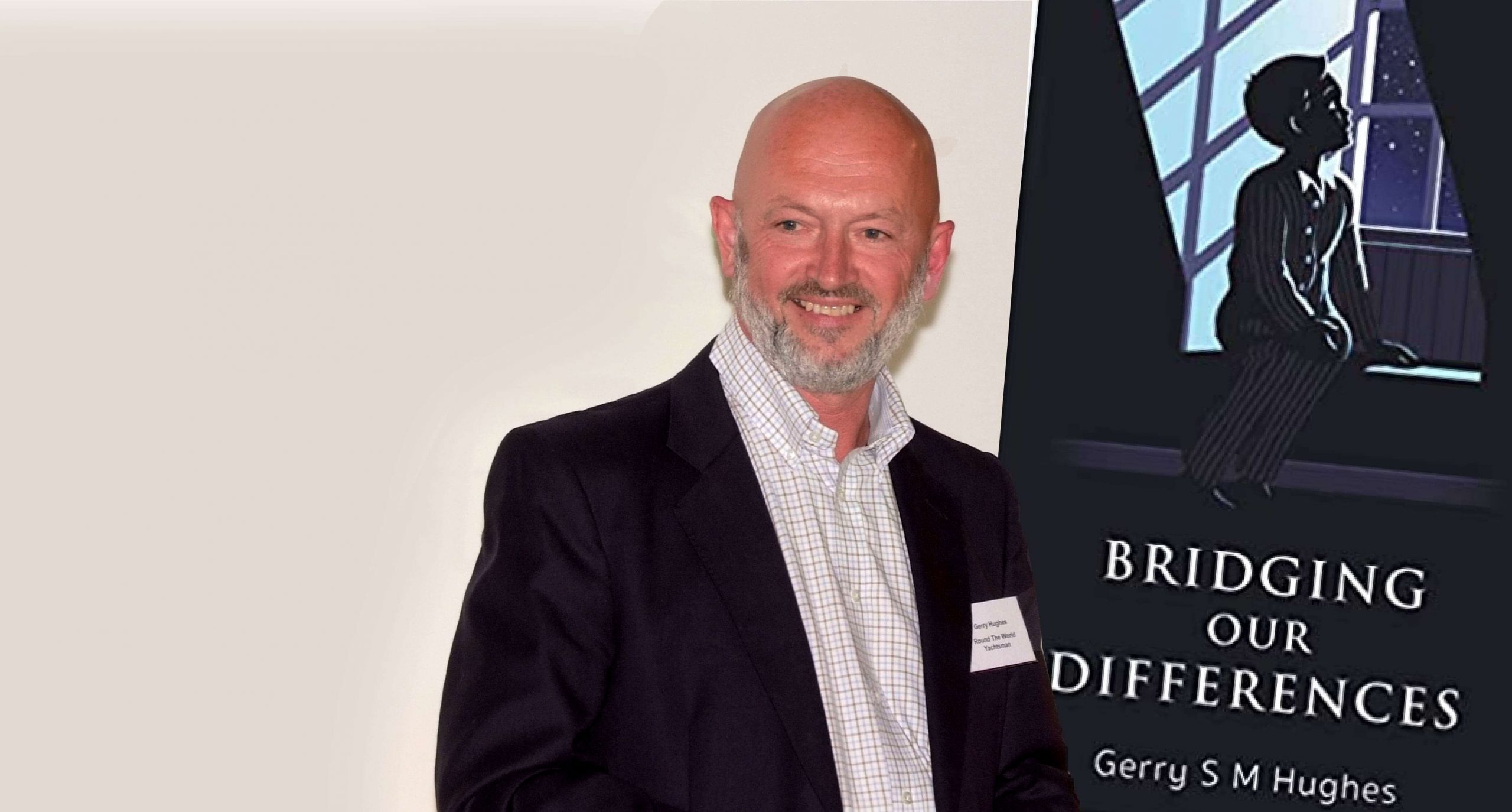

Glaswegian Gerry Hughes is the world’s first deaf elite solo circumnavigator. More than that, he is a role model to the global deaf community.

“One day I will go like Sir Francis”

Glaswegian Gerry Hughes is the world’s first deaf elite solo circumnavigator. More than that, he is a role model to the global deaf community. Not only have his world record-breaking sailing achievements been self-funded, and the result of personal determination, his commitment to improving the life chances of deaf children means that he is firmly established in the history of disabled rights in education and sport.

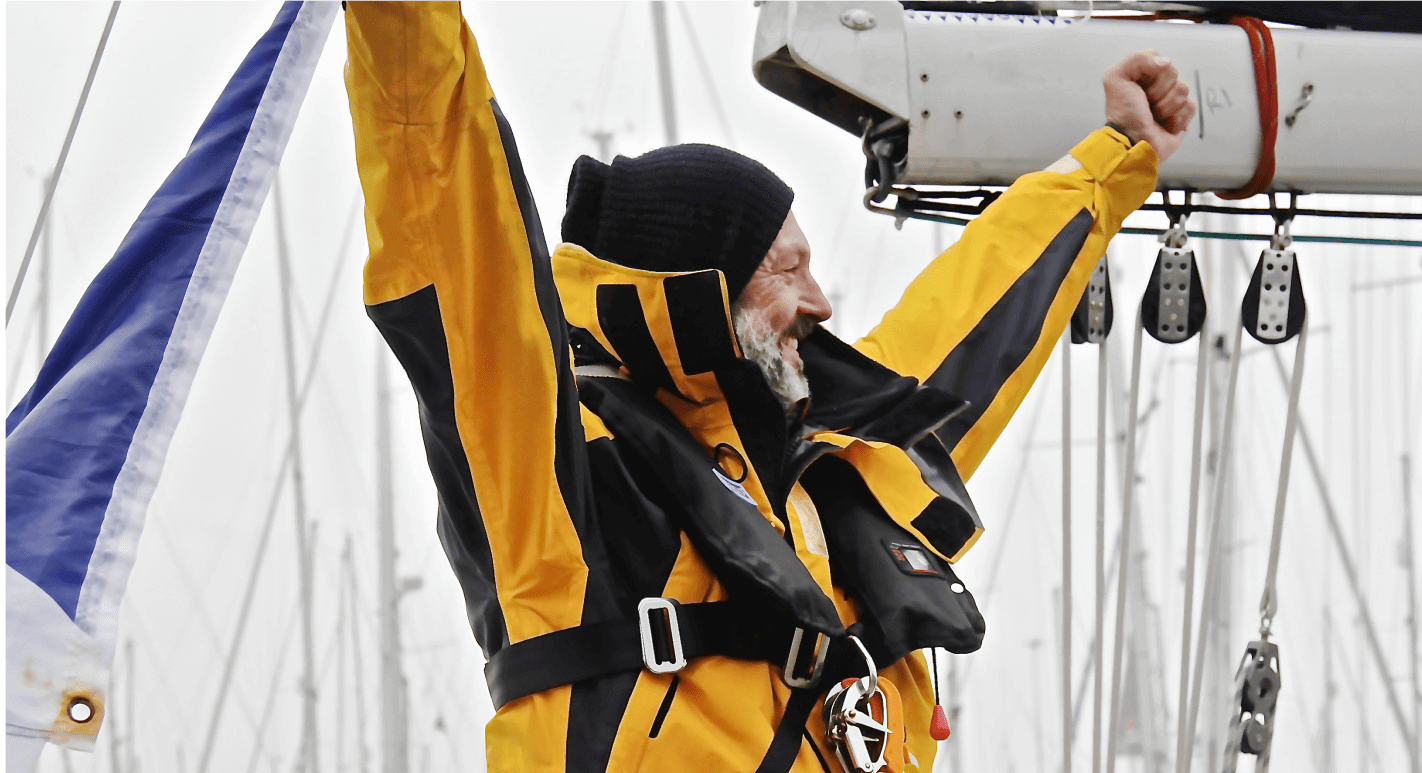

Gerry secured his place in sporting history by becoming the first profoundly deaf man in the world to complete a solo circumnavigation of the world via the Five Great Capes.

This particular route is the most challenging and dangerous route any yachtsman can take, and the only one that allows entry to the Slocum list of Solo Circumnavigators.

The significance of this achievement can easily be put into context: more people have been in outer space than achieved this feat. Gerry not only secured his place as an elite solo circumnavigator, but because he is deaf, he is did this without the access to VHF Radio Communication. In addition, Gerry’s Quest III adventure was truly a solo venture. Gerry had no sponsors so he used his life savings to buy a Beneteau 42s7 and spent two years modifying the boat himself to ensure it met ocean safety standards. This, in itself, is testimony Gerry’s sailing expertise. Gerry spent months and years preparing for his Quest III adventure: researching weather and sea conditions; nutritional requirements; and honing his sailing skills to be able to take on such a challenge.

Gerry Hughes has spent his life breaking down barriers. Gerry was born in Glasgow. He is profoundly Deaf and communicates in BSL. Despite learning to sail at the age of 2, he struggled to learn read and write until the age of 15. This was the result of the Milan Convention of 1880, which led to the banning of sign language in deaf schools across the world and the prohibition of deaf people from working as teachers. Instead, the oralist philosophy of deaf education insisted that deaf children must use their residual hearing to ‘listen’ and that they must learn via lipreading. Sign language was strictly forbidden, and parents of deaf children were advised not to use sign language at home. Children were punished if teachers caught them using sign language.

But Gerry was no ordinary child. Gerry’s father had been in the Royal Navy and recognised Gerry’s remarkable prowess in sailing from a very young age. Not only was Gerry was a gifted navigator, he could predict the weather from the swell of the sea and watching the clouds. Despite this, Gerry could not tell his father the name of the street in which he lived. It was then that Gerry’s parents made the heart-breaking decision to move Gerry to a specialist residential school in England in an attempt to ensure that their only child had a chance of an education. The head teacher at this school also recognised Gerry’s potential and realised that while Gerry could say the words on the page, he did not understand their meaning. It was then that she decided to spend and 30 minutes every day with Gerry teaching him to read and write. After 18 months of hard work, Gerry finally began to understand the words in front of him. He was desperate to demonstrate his new skills to his parents at the next school holidays. But, when he arrived home, he realised that the sailing books by the fireside where too difficult for him to understand. Gerry furiously searched for something that he could read to his parents. He found a magazine about Sir Francis Chichester. Gerry wrote a note to his father on the magazine. It was the first message to his father in which Gerry truly understood the meaning of the words he had written: ‘one day I will go like Sir Francis’.

Gerry knew that education was the key to achieving his sailing ambitions. But his experience of the education system also meant Gerry was determined that deaf pupils should not have to go through the same traumatic experiences of his childhood education. In 1979 Gerry secured a place at Langside college to study for Scottish Higher qualifications. After obtaining the qualifications necessary to enter teacher training college, and passing the interview, Gerry was refused a place on the course because he is deaf. This triggered Gerry’s relentless campaign against the regulations that prevented deaf people entering the teaching profession. In 1995 became the first deaf BSL user become a qualified, registered teacher in Scotland since the Milan Convention of 1880. In 2007, Gerry became the first Deaf person in Scotland to attain Chartered Teacher Status (via Master’s Degree).

In 1981 Gerry accepted a post as a research associate with at Moray House Education, University of Edinburgh. The research team led by Dr Mary Brennan was analaysing the linguistics of British Sign Language (BSL). This was to be the turning point in Gerry’s life. Dr Brennan’s research confirmed that BSL is a ‘real’ language with its own linguistic features such as grammar and syntax. As Gerry’s understanding of sign language linguistics deepened, he realised that BSL was the key to his understanding of the world around him. Gerry had discovered his identity: a deaf BSL user. Armed with the knowledge that his native language “British Sign Language” was equally valid to spoken English, he had the confidence to move towards achieving his ultimate dream. In 1983, Gerry became Director of Quest for a Language – developing and managing a sign language curriculum. This (and his work at Moray House with Dr Mary Brennan) was an essential component underpinning to the current BSL curriculum.

Gerry never lost sight of his sailing ambitions. In 1981 Gerry and his mate Matthew Jackson circumnavigated the islands of the British Isles in Faraway II (a Westerly Longbow, 31 feet). In doing so, Gerry became the first deaf skipper to circumnavigate the British Isles without communication aids: they heard no weather forecasts, nor could they use VHF Radio or RDF Beacons.

In 2005, Gerry became this first deaf skipper to sail across the Atlantic Ocean in the Original Single-Handed Transatlantic Race (OSTAR), 2005 in his boat Quest II -a Rodger OOD34 (Offshore One Design). It was a difficult sail. Gerry and Quest II had a complete electronics breakdown, spent 21 days at sea in severe gales and intermittent fog and with no means of communicating with the shore. The race organisers considered Gerry to be ‘lost at sea’ and formally announced that they did not expect Gerry to arrive at the finish line. But despite no means of communication and no navigation equipment, Gerry kept going, relying on the navigation skills his father taught him. Gerry achieved 16th place amongst the 42 boats in the Corinthian Race. He was named ‘Spirit of the Corinthian’, for OSTAR 2005 for his bravery and skills in navigation.

In May 2013, Gerry achieved his third Quest – sailing round the world solo via the Five Great Capes. His progress throughout this epic voyage was followed by thousands of people around the world via his website and Facebook page. Schools started following Gerry’s voyage and it became the focus that engaged pupils in their Geography lessons. Students of Sign Language logged into Facebook to follow his progress to learn and engage with the global deaf Community. Meanwhile, far out at sea, Gerry was unaware of the impact he was having.

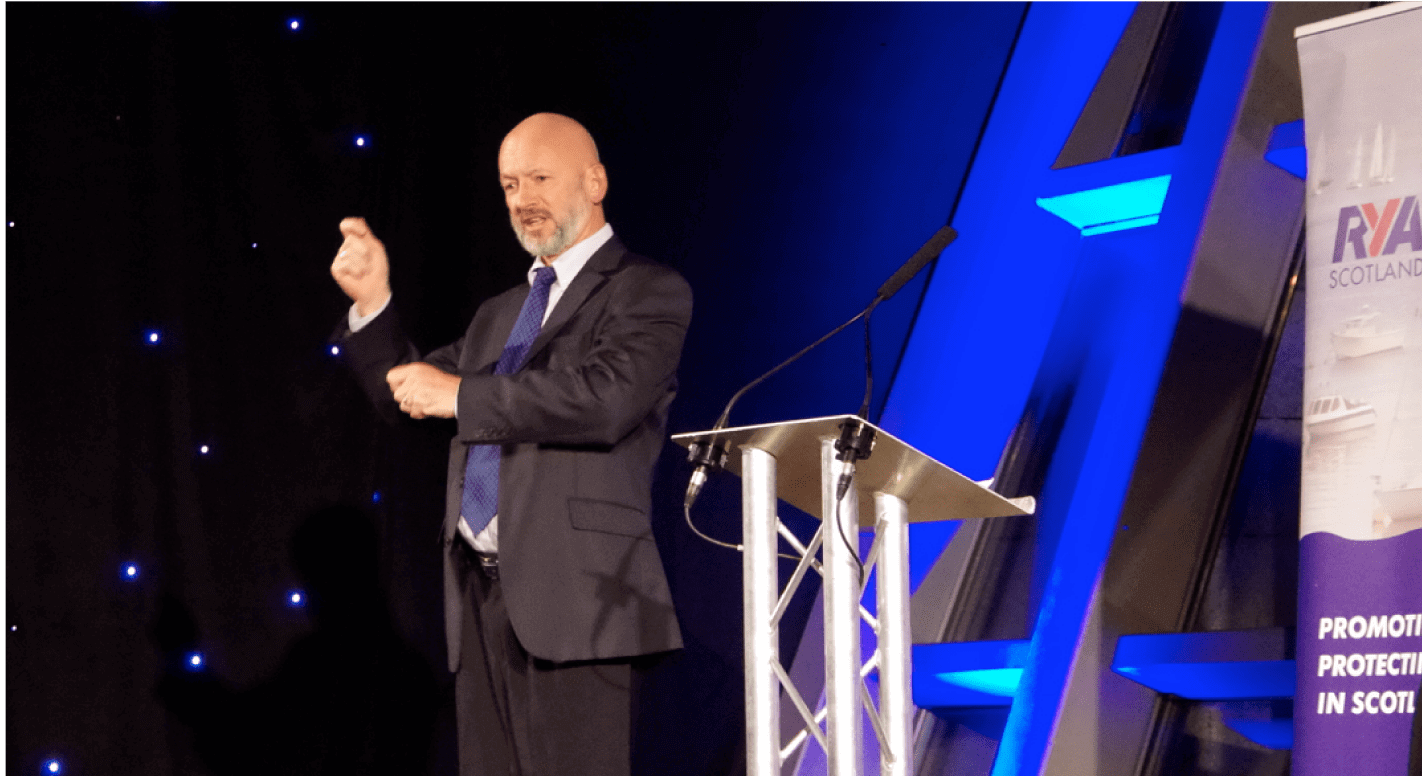

Gerry has received many honours and awards in recognition of his achievements. The RYA Sailability Personal Endeavour Award was created in recognition of Gerry’s enduring determination and skills in sailing. In 2013, Gerry was awarded the Todrick Trophy and made an Honorary Life Time member of the Clyde Cruising Club in 2013. He also received the Lord Provost Award for Glasgow Sports Person of the Year 2013. Gerry is an Honorary Member of the Merchants House of Glasgow, Lifetime Honorary member of the Clyde Cruising Club and member of the International Association of Cape Horners. In June 2014, Gerry was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of Glasgow in recognition of his contribution to education, disabled rights and sport.

In addition to his passion for sailing, Gerry is an accomplished golfer. He has played golf for Scotland in the World Deaf Golf Championships six times. Gerry was granted Honorary Lifetime Membership of Cathkin Braes Golf Club in December 2021.